By Joe Wasp for Identity Dixie

We here in Southern Nationalist circles, and the more competent sections of the Dissident Right, are all too familiar with trending narratives on Southern, especially Confederate, imagery. The history surrounding the public displays of Confederate symbols and the narrative of said historiography has been on my mind as of late. I will admit that much of this has been spurred on by my love for rock and heavy metal and the once pervasive utilization of the Confederate flag among bands, in addition to my seeking out of now difficult to acquire Confederate merch of some of those bands, such as Pantera and Lynyrd Skynyrd. Casting a more formal essay style to the side, I will discuss here much of the heretofore forgotten history I have managed to find of the campaign against Confederate symbols.

The campaign against Southern iconography truly began in the 1980s at the local level. The attacks against the Confederate flag are difficult to research during this period due to them being quite small in scale, piecemeal, and wildly unpopular on the occasions they happened, but there were certainly nefarious schemes at the time, nonetheless. The best provable moment of this occurring took place in 1982 at Ole Miss, once the one of the crown jewels of Southern public education and a historically prideful flagbearer, pun intended, of the Southern tradition. The attack was two-pronged and wholeheartedly manifested within the Ole Miss sports sphere. To my amazement, there is an easily accessible article discussing this with some eyebrow raising bits of information which lead interesting inferences. Furthermore, the Colonel Reb Foundation, a group seeking to preserve the renowned mascot’s legacy and existence, also has some history on this matter here and here.

While some other protests were occurring on campus regarding tailgating at the Grove, or “Groving,” the most impactful “protest” came from an individual by the name of John Hawkins. The first Negro member of the Ole Miss cheerleading squad, Hawkins made waves due to his refusal to carry the Confederate flag onto the football field. For all of his grandstanding and attempts at recognition, he made an interesting comment on his actions, stating, “While I’m an Ole Miss cheerleader, I’m still a black man. In my household, I wasn’t told to hate the flag, but I did have history classes and know what my ancestors went through and what the Rebel flag represents. It is my choice that I prefer not to wave one.” This move came completely out of nowhere, as Ole Miss had been integrated in 1962, 20 years prior, and no issue had been made regarding the university’s use of Confederate imagery by black students. It is also worth noting that he stated how he was not raised to hate the flag, bringing in to question whether or not he was being told to say and do this. This statement, along with other quotes from blacks, indicate the much more amicable existence between Whites and Negroes in Dixie prior to the 21st Century.

With the exception of John Hawkins, nearly 100% of all anti-Confederate anti-Colonel Reb protests came from the sports cadre and school dictators administrators. Not one single instance of removing Southern imagery and culture, be they the Confederate flag, Colonel Reb, or the band playing “Dixie,” have proved even remotely popular among students and fans alike.

The 1990s marked the beginning of major establishments and the media’s attacks on the Confederate flag and encompassed what I often refer to as the “Third Reconstruction.” Whereas a few attacks took place in the 1980s, they were largely inconsequential, and there was a much more optimistic mentality in Americans as a whole during the Ronald Reagan years. Additionally, the 1980s saw a revival of pro-Southern music and representation in various forms of entertainment, with a notable lack of anti-Southern filmography during that decade. The 90s sharply diverged from this trend.

It was during this decade that a tidal wave of simultaneous attacks from state governments, local leaders, university administrators, and the media occurred so as to paint Southerners, and their symbols, in a negative light. Ole Miss banned flag waving, especially targeting the Southern Cross, at its ballgames and ceased production of Confederate themed memorabilia so as to distance itself from the Southern university image it had so long been viewed as. Television shows regularly began painting Southerners as bumbling, violent morons, often inbred, and racists, a trend not seen since the 1970s. The X Files comes to mind.

The most notorious instance of the media’s anti-Southern bias falsely mischaracterizing someone came about during the fallout of the Centennial Olympic Park bombing in Atlanta, Georgia in 1996. I will not go into full detail here, but this article does justice to the events which transpired. Richard Jewell saved hundreds of lives during the Atlanta Olympics but was brought through the ringer by the news media and FBI because he fit the typical Southern stereotype. His truck’s front plate being the 1956 Georgia Flag was plastered all over the television, and he was often referred to as the “Una-Bubba” and “Bubba the Bomber.” More attempts were made to paint him as a militia supporting, terrorist seeking fame as a hero after placing the bomb at the stadium himself, playing into the fears of the Militia Movement of the time and the recent memory of the Oklahoma City bombing. He would, of course, be exonerated after the real bomber was found, but this showed the length to which the media would go to paint a malevolent view of Southerners after largely having not done so since the 1970s.

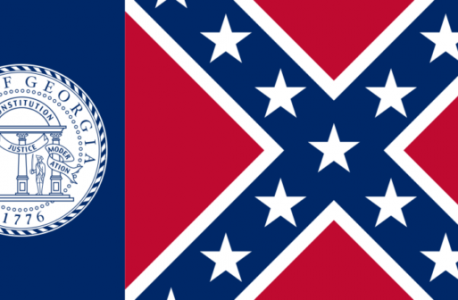

The campaigns against state usage of Southern imagery catalyzed unilaterally and concomitantly across Dixie. Taking advantage of the retirement and “assumption of room temperature” of the few remaining Southern Democrats, like John Stennis and James Eastland, Southern legislatures undertook measures, without previous warning, to eradicate public displays of the Dixie Cross. Jim Folsom Jr. of Alabama, within six days after assuming the governorship, removed the Battle flag from the state capitol. Mississippi’s and Georgia’s legislatures began massive campaigns to change their respective state flags. Governor Kirk Fordice of Mississippi, serving from 1992 to 2000, was a staunch conservative and spared Mississippi from much of the liberalizing of the time. He was elected as a backlash of sorts against the vehement attempts from Democrat Governor Ray Mabus to liberalize the state as part of the greater Democratic trend occurring in the South with the departure of the aforementioned Conservative Southern Democrats. Mabus was described as “arrogant and out of touch with Mississippi politically” by Kirk Fordice in the 1991 election campaign and was even described by The New York Times as a “Porsche politician in a Chevy pickup state.” Georgia did not fare so luckily. However, the most notable of these moves came about in the Palmetto State and Georgia.

The NAACP, after a tumultuous period of changes in leadership, crippling debt, poor organizing, and a lack of direction, came out swinging in South Carolina in 1999. Adopting the eradication of Southern imagery as its strategy after lacking a bit of direction following the Civil Rights Movement, the organization campaigned hard to have the Battle flag removed from the South Carolina capitol building. Democrat Governor Jim Hodges would buckle to pressure from activist groups by officially recognizing MLK Day and removing the flag from the capitol building. However, he did compromise by officially recognizing Confederate Memorial Day and simply moving the battle flag to the capitol grounds.

In 2001, the Democrat controlled Georgia State Assembly made the decision to change the state flag after years of pressure from media groups and the NAACP, under the direction of Democrat Governor Roy Barnes. He replaced it with an awful looking flag and lost the next gubernatorial run, as a direct response to his flag decision, against Republican Sonny Perdue, who endorsed the current state flag and had it adopted via a popular vote in 2003.

As an interesting note about the NAACP, it did not so intensely attack Confederate imagery until the mid-to-late-1990s. After the Civil Rights Era, it had little of significance to actually do, and it did little to actually improve the lives of “Colored People.” It, along with the SCLC (Southern Christian Leadership Conference), had to remain relevant so as to continue receiving donations and funds, thus beginning its campaign against Southern images and culture in the 90s. Prior to this period, as previously mentioned, race relations in the South were fairly peaceful, and blacks did not so toxically hate Confederate imagery and its supporters.

Each and every respective instance of anti-Confederate, anti-Southern campaigns in Southern states carried out by Democrat governors and state legislatures during the 1990s and early 2000s led to the turn of these states to the Republican Party within the following gubernatorial election cycles. Jim Folsom Jr. in Alabama, Roy Barnes in Georgia, and Jim Hodges in South Carolina would all be the last Democrat governors of their states. The last to turn Republican was Mississippi, after Democrat Governor Ronny Musgrove would put the state’s flag to a referendum vote in 2001, being replaced by Republican Haley Barbour in 2004.

After 9/11, affairs returned to normal. The War on Terror distracted the Left for a generation and brought the Third Reconstruction to a close. Despite all of the Left’s efforts, the Confederate flag remained quite popular. Many continued to defiantly sport it during the 1990s and 2000s largely due to the still strong Southern culture and the attitude many still had to resist being told what to do. It was very common to still see battle flags flown at various rock, metal, and country concerts. Down, Pantera, and Lynyrd Skynyrd are but a few examples of this greater cultural shift in music, and the latter two sold a plethora of Confederate themed merchandise. Yet, Ole Miss did remove Colonel Reb as its official mascot in 2003, angering many. No mascot Ole Miss has produced since has achieved the popularity to culturally replace the iconic Colonel Reb.

The Obama Era changed things rapidly. It was during this time that the South changed greatly. Homosexuality was promoted in full force, and the president himself would openly, on live television, chastise Christian Whites, rural folk, and the traditions of both groups, stating that “they cling to their guns or religion.” What remained of Southern vernacular and accents began to quickly disappear, and it seemed as though every aspect of life took on a malicious post-modern “feel.” Public displays of Confederate imagery came under scrutiny once again. One of the more notable examples was within the aforementioned rock and metal communities. Long a symbol correlative with those genres, publications started demeaning the industry for its plethora of Southern themed merchandise and concert flag waving. Lynyrd Skynyrd infamously declared their reservations about waving the Southern Cross at concerts in 2012, to the uproarious chagrin of its fanbase, and many metal bands began quietly putting away the imagery starting around 2010. This would be piecemeal until 2015, following the Charleston Church Shooting. Afterward, the Fourth Reconstruction started, and the rest is history.

Little more may be said here. The campaign against Southern imagery precedes 2015. This is well known, but I have noticed a lack of discussion of its history and some of the finer details of it as well as the malignant tomfoolery going on behind the scenes.