By Spencer J. Quinn for the Occidental Observer

The Transfer Agreement

Edwin Black

Dialog Press, 2009 edition.

When you write a polemic, one meant to justify victory in a war, it would be best to deliver checkmate—that is, irrefutable proof that the correct side had won and that lives had not been sacrificed in vain. Edwin Black’s 1984 volume The Transfer Agreement, which chronicles the secret pact between the Third Reich and Jewish Palestine, is one such polemic. It’s filled with nail-biting drama and larger-than-life characters; it gives us suspense and intrigue, and embodies the agony and ecstasy of Jewish triumphalism on almost every page. As far as histories go, it’s well-paced, extensively researched, and thought-provoking. Ultimately, however, it delivers everything but checkmate.

Indeed, if anything, The Transfer Agreement casts a sympathetic light on the Nazis and reveals how unnecessary, preventable, and essentially Jewish the Second World War really was.

All of this, of course, is unintentional. Black asserts in his Introduction to his 2009 edition that just because Nazis worked with Zionists in the 1930s to establish the commercial, financial, and industrial infrastructure which would become the backbone of Israel does not mean that the Nazis deserve praise or are no longer the despised enemies of humankind. The cognitive dissonance of such a relationship apparently caused Black much anguish and confusion. Yet he persevered to tell this painful yet utterly crucial story of Jewish redemption:

The message of The Transfer Agreement was in fact the chronicle of the anguish of choice—itself the quintessential notion of Zionism’s historical imperative. This book and its documentation posit one question: when will the Jewish people not be compelled to make such choices? Indeed, when will all people similarly confronted be freed from the desperation of such choices?

I know. I gagged too. Dressing up Jewish causes as universal while ignoring or dismissing equally urgent white European causes is a tack Black resorts to often in The Transfer Agreement. For example, in the book’s Introduction, Black lies thusly:

The Zionists were indeed in the company of all mankind—with this exception: The Jews were the only ones with a gun to their heads.

That Black ignores how the disproportionately Jewish Bolsheviks had conquered Russia and contributed to the murder or starvation of millions of Soviet citizens prior to Hitler’s rise to power in 1933, reveals the fundamental dishonesty of The Transfer Agreement. A gun was certainly pointing in the other direction as well.

Such a batter mixed with half-truths can only result in a half-baked product, which makes The Transfer Agreement such a frustrating read. Yet, like Black himself, I persevered. I persevered to reach the inevitable conclusion which Black so unwittingly draws: that without the vituperative neuroticism of a worldwide network of Eastern European Jews, the Second World War would never have happened, and tens of millions would not have died for nothing.

The opening chapters strike one most for the sheer bellicosity of American Jews who immediately found the chancellorship of Adolf Hitler intolerable. Also on display was their awesome power. Rabbi Stephen Wise of the American Jewish Congress (AJC) spoke the loudest and with the greatest scorn, and soon influential Jews across America were debating whether to instigate a comprehensive boycott of Germany. These were no idle threats. Jews controlled many industries, including much of the press, even back then. With enough agitation from the right people, whole cities could rise up in protest against the Third Reich.

If there was any European country back then that could not afford to be boycotted, it was Germany. With millions unemployed and the nation wracked with inflation, Germany was still struggling to pay its war reparations stipulated in the treaty of Versailles. The 800,000 Germans who died of malnutrition at the end of the First World War due to the Allied blockade, as well as the French invasion of the Ruhr in 1923, were still fresh in the minds of many. Things were economically miserable in Germany, and with millions of jobs dependent upon the foreign market, “export was the oxygen, the bread, and the salt of the German workforce. Without it, there would be economic death.”

Black explains further:

Just before the decade closed, on October 24, 1929, Wall Street crashed. America’s economy toppled, and foreign economies fell with it. For Germany, intricately tied to the all the economies of the Allied powers, the fall was brutal. Thousands of businesses failed. Millions were left jobless. Violence over food was commonplace. Germany was taught the painful lesson that economic survival was tied to international trading partners and exports.

So when American Jewish Congress (AJC) vice-president Joseph Tenenbaum threatened that “[a] bellum judaicum—war against the Jews—means boycott, ruin, disaster, the end of German resources, and the end of all hope for the rehabilitation of Germany.” Hitler, the Nazis, and the suffering German people who elected them knew right away that they were beset by powerful enemies bent upon their utter destruction. Of course, such men were not peculiar to America. Black chronicles how the anti-Nazi boycott movement spread quickly around the world, gaining traction in Europe, the Middle East, and South America. Further, the movement was well-funded and organized with protestors often looking to the AJC in New York for cues.

The alacrity and vehemence with which the Jews reacted to Hitler’s ascension to power were indeed astonishing. With Hitler’s chancellorship not even six-months old, the anti-German boycott had already cost the Third Reich hundreds of millions of Reichsmarks.

One curious aspect of this was Poland. Black does not go into it as much as I would have liked, but he asserts in several places that Polish Jews were indeed behind Polish anti-German truculence throughout the 1930s. The Jews of Vilna were especially vicious, and soon infected the rest of Poland with anti-Nazi fever, which they quite shrewdly framed as national rather than ethnic. The protests quickly grew violent, and in Upper Silesia became “altogether unbearable” according to the German Foreign Ministry. Adding to the insult, the Polish Undersecretary of State told Reich Ambassador Hans Moltke that the Polish government was uninterested in interfering with the boycott.

While Black provides many details surrounding anti-Jewish attacks in Nazi Germany, he offers none on anti-German attacks in Poland, other than that they were “violent.” Things grew further out of hand as Poland, along with Czechoslovakia, began rattling sabers after Hitler, according to Black, threatened to “seize the Versailles-created territorial bridge” (i.e., the Polish Corridor). This led to Poland’s militarization of its western border and serious talks about invading Germany while it was still weak. Thus, the image of Poland being the poor and innocent victim of Nazi aggression gets exploded on the pages of The Transfer Agreement.

We can also thank Edwin Black for writing the following three enlightening sentences:

Polish Jews had successfully enflamed Poland from defensive concern to war hysteria through their violent anti-German boycott and protest movement. German officials were in fact astonished that the historically anti-Semitic Polish people would allow Jewish persecution in Germany to become the pretext for a war. But it was happening.

Why were Jews everywhere so distraught? Hitler barely had time to get his seat warm in the chancellor’s office when Jews were already declaring him an unmitigated catastrophe and were mobilizing with the utmost urgency. Well, according to Black in numerous places, Adolf Hitler had already planned the complete destruction of German Jewry, so the Jews had no choice but to strike back as hard as they could in self-defense. And boycott, along with disruptive protests, picket lines, public humiliations, and libelous editorials were their weapons of choice. “Germany,” Black declares, “would have to be crushed, not merely punished.”

Yet according to the Jewish Encyclopedia, Black’s accusations of Nazi genocidal plans back in 1933 are simply not true.

Did the Nazis always plan to murder the Jews? No. When the Nazis came to power in Germany in 1933, they did not have a plan to murder the Jews of Europe. However, the Nazis were antisemitic. They saw Jews in Germany as a problem. One of the major questions for the Nazis was: How do we get rid of the Jewish population in Germany?

One finds this fairly often in The Transfer Agreement. Black will make some hysterical claim and then footnote it with a source that does not support his hysterical claim. For example, after a brief biography of German banker and early Hitler ally Hjalmar Schacht, Black writes:

It was Schacht who now pledged to his Führer to reestablish Germany’s financial integrity and build a war economy designed for territorial and racial aggression.

Neither of his sources—William Shirer’s The Rise and Fall of the Third Reich (1960) and Schacht’s 1956 autobiography Confessions of “The Old Wizard”—mention anything about “racial aggression” on the pages Black specifies (204–205, 265–266, 284, and 358–359 for the former and 2, 6, and 14 for the latter). Shirer does claim that Schacht was most helpful in “furthering [Germany’s] rearmament for the Second World War”—as if Hitler and the Nazis were plotting Stalingrad and the Battle of Britain way back in 1933. But unlike Black, Shirer does not even offer footnotes. So Black bases his assertion on Shirer’s, which is, it turn, baseless.

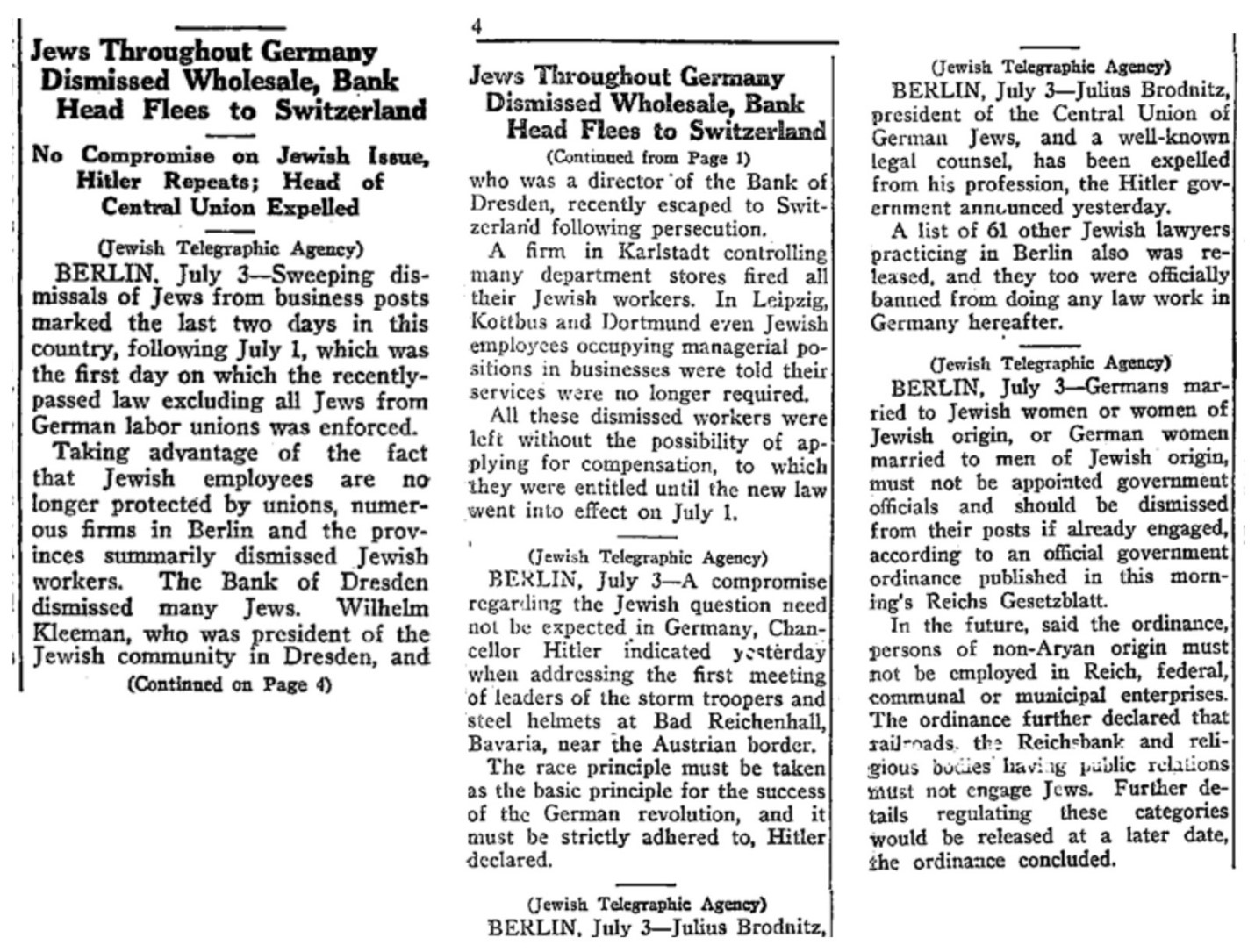

Black’s most astonishing faux pas occurs on pages 262–263 in Chapter 28. He writes:

At the height of Germany’s unemployment panic, on July 2 Hitler reassured a nationwide gathering of SA leaders that while the tactics might become more restrained, there was no thought of altering the ultimate goal of National Socialism: the speedy annihilation of Jewish existence.

Black’s lone source for this is an article entitled “Jews Throughout Germany Dismissed Wholesale, Bank Head Flees to Switzerland” from the Jewish Daily Bulletin, July 5, 1933. Here is the link, and below is a reproduction of the article itself. See if you can find anything about the “speedy annihilation” of Jews.

Perhaps this was a simple error, but it survived till the 2009 edition which was published 25 years after the first. And it is a pretty big error to boot.

Black also lacks self-awareness in spots, at times argues against himself—which only makes him look foolish. He glorifies the anti-German boycott often in the Transfer Agreement, and approvingly relays a story in which AJC vice-president W.W. Cohen shouted “No!” at a restaurant when the waiter offered him an imported Bavarian beer. Afterwards, Cohen attended a rally and announced that “any Jew buying one penny’s worth of merchandise made in Germany is a traitor to his people!” A few pages later, after the Germans quite understandably respond in kind against German Jews, Black is suddenly against boycott and wishes to direct our sympathy towards its innocent victims:

But this boycott would be a systematic economic pogrom that would plague every Jewish business and household. No one would be spared. What professional could survive if he could not practice? What store could survive if it could not sell?

This obvious double standard is so appalling that not only should Black not be taken seriously whenever he demonizes Nazis or complains about anti-Semitism, neither should his publisher or editors. Here are three more examples that remove any doubt that Edwin Black is little more than a shameless shill for the Jews.

On page 78, he claims without a source that the Nazis “regarded the Zionists as their enemy personified, and from the outset carried out a terror campaign against them in Germany.” But on page 175, he changes his tune and states how Zionist German Jews actually enjoyed more freedom under the Nazis than did non-Zionist Jews. The Zionist newspaper Juedische Rundschau was allowed relative press freedom; Hebrew was encouraged in all Jewish schools; Zionists were allowed to raise a Star of David flag when ordinary Jews were not allowed to raise the Swastika; and youth groups were permitted to wear Jewish uniforms, “the only non-Nazi uniform allowed in Germany.”

Some enemy. Some terror campaign.

Chapters 18 and 28 also shed harsh light on Black’s blatant hypocrisy. In the former, he congratulates the Jews for going global with their pro-Jewish, anti-Nazi vitriol, and in the latter, he frets over how anti-Jewish and pro-Nazi movement was going . . . wait for it . . . global.

Further, on page 25, Black writes [emphasis mine]:

But when Hitler and his circle saw Germany deadlocked in depression, they did not blame the world depression and the failures of German economic policy. They blamed the Bolshevik, Communist, and Marxist conspiracies, all entangled somehow in the awesome imaginary international Jewish conspiracy.

At this point, Black’s editors, proofreaders, research assistants, or the publisher himself should have taken their clueless author aside and gently reminded him that his entire book is about an international Jewish conspiracy. Just about on every third page you have Jews in one country or continent writing, phoning, or cabling Jews in another country or continent. The big meetings in Prague and Geneva which Black reports on late in his book consist of Jews from all over the place arguing over how best to smother the Third Reich in its cradle. How is this anything other than an international Jewish conspiracy?

How could Edwin Black not see how much of The Transfer Agreement not only justifies some of the worst anti-Jewish stereotypes, but also exonerates the Nazis for understanding the truth about Jews and frankly being so patient with them?

Here is a list of all the things Black records in The Transfer Agreement which point to the Nazi leadership being at least somewhat reasonable—not necessarily innocent, mind you, but reasonable—in the face of international Jewish pressure:

- Hitler, Hermann Goering, and other high-level Nazis demanded that Nazis not commit acts of violence. (pp. 49, 52)

- Hitler promised not to boycott German Jews only after world Jewry stop boycotting the Third Reich. (pp. 59–60)

- The Nazis provided special treatment for German Zionist Jews, as mentioned above. (pp. 174–175)

- In June 1933, Hitler personally allowed the AJC and other groups to send a multimillion-dollar relief fund to German Jews. (p. 185)

- After Hitler called off the April 1 anti-Jewish boycott, provincial Nazis continued to boycott Jews despite orders from Berlin not to do so. (p. 219)

- Hitler bailed out a large Jewish-owned department store chain and then strictly forbade mass arrests and harassment of businessmen and industrialists. (p. 220–221)

- In order to outlaw atrocities, suppress anti-Jewish acts, and prevent a “second revolution” by fanatical Nazis, Goering ordered mass arrests of dissident Nazi units. (p. 223)

- Goering promised the death penalty for “atrocity mongers” among the Nazi rank and file. (pp. 224–225)

- When followers of Der Stürmer publisher Julius Streicher illegally arrested 300 Jewish shopkeepers, the authorities released them immediately. (p. 224)

- The Nazis actually encouraged Jewish religious, cultural, and athletic activities in the cities. Black writes: “The Nazis delighted in the Jewish subculture and demanded that it thrive. Indeed, every Jewish gathering was approved and attended by Gestapo. For Aryans, an active Jewish subculture provided reinforcement that Jews were an alien people who had no place in Germany.” (p. 373)

Black’s own analysis reveals that the Nazi leadership at least made an effort to crack down on their own radical followers. It seems that a good deal of the atrocity propaganda Black cites from 1933—minus all exaggerations and lies—happened in spite of Adolf Hitler not because of him. Yet none of this means a whit to Black. The Nazi leadership should be condemned as guilty not for what they were doing in 1933 but for what they were going to do ten years later.

This is entirely unreasonable, and it ignores the role the Jews themselves played in so maliciously provoking war with Germany throughout the 1930s. What I wrote about Benjamin Ginsburg’s How the Jews Defeated Hitler—another book about 1930s Jewish warmongering—applies also to The Transfer Agreement. And it has everything to do with legerdemain:

How does a magician cause objects to vanish or appear out of nowhere? Through a technique called misdirection, he can draw your attention away from something magical that is about to happen by manipulating your ability to anticipate or remember. In a sense, the magician interferes with your sense of time. Ginsburg and other authors accomplish a similar sleight of hand when discussing Nazi Germany prior to the war. According to their specious logic, because the Nazis committed war crimes during the war, the Nazis must also be considered guilty of the same crimes before the war. Therefore, promoting war against the Nazis during the 1930s is perfectly justified and honorable.

Again, this is not to say that the Nazis were entirely innocent or didn’t say or do horrible things to Jews. They certainly did. They were socialist totalitarians, and so could act with ruthless, top-down efficiency when they wanted to. By virtue of being both eugenic-minded and pro-German in nature, they took a dim view of the subversive Jewish outgroup. Hence the unsubtle hints for Jews to leave; hence the transfer agreement. But did some Nazis do heinous things? Sure. I think it is safe to assume that not all of the reports of murders, beatings, incarcerations, and other outrages were lies or embellishments. Furthermore, Nazi leaders starting with der Führer himself said a few things you just can’t easily unsay.

On page 62, Black describes how Hitler raged in the presence of the Italian ambassador when informed of Mussolini’s disapproval of Nazi anti-Semitism:

“I have the most absolute respect for the personality and the political action of Mussolini. Only in one thing I cannot admit him to be right and that is with regard to the Jewish question in Germany, for he cannot know anything about it.” Hitler continued that he alone was the world’s greatest authority on the Jewish question in Germany, because he alone had examined the issue for “long years from every angle, like no one else.” And, shouted Hitler, he could predict “with absolute certainty” that in five or six hundred years the name of Adolf Hitler would be honored in all lands “as the man who once and for all exterminated the Jewish pest from the world.”

Such a statement is impossible to defend—and yes, I went to the source, and it checks out (John Toland’s 1976 Adolf Hitler, p. 325—although Black mistakenly lists it as page 424). Hitler did say this. Immense moral quandaries aside, if you agree with such a genocidal statement, then you are giving Jews like Stephen Wise all the reason they need to act preemptively against Germany and with extreme prejudice. After all, in a fight, one’s opponent has the right to fight back.

The best way to address this conundrum is to allow Black to lead us to deep water, and then go deeper, where he is unprepared to go. Why were so many Germans, and Nazis in particular, so indignant about the Jewish presence in Germany? Why would Hitler declare such enmity for Jews and not for any other non-Aryan ethnic group in Germany?

Well, given that all the negative stereotypes about Jews back then—usury, alcohol peddling, prostitution, pornography, business tribalism, etc.—can arguably be balanced by their accomplishments in a host of other fields—including medicine, science, and music—the best way to respond would be to point to the Soviet Union and all its unspeakable enormities as a model of Jewish supremacy. Then we can ask why the protagonists of The Transfer Agreement—as well as Black himself—never suggest that perhaps the millions of people already slaughtered or starved by the disproportionately Jewish Soviet leadership by 1933 was the reason the Nazis had such a massive a chip on their shoulder. As Michael Kellogg demonstrated in his 2005 The Russian Roots of Nazism, the Nazis were well aware of the apocalyptic nature of Bolshevism as well as its undeniable link to Jews. They did not want what happened in 1917 Russia to happen in 1933 Germany. And who can blame them?

Hitler said he wanted to exterminate the Jewish pest? Fine. In his 1990 work Stalin’s War Against the Jews, author Louis Rapoport quotes Jewish Politburo member Grigory Zinoviev saying the following in 1917:

We must carry along with us ninety million out of the one hundred million Soviet Russian population. As for the rest, we have nothing to say to them. They must be annihilated.

And you know what? The tragic irony here is that Zinoviev was underselling the destructive power of his own government. Had only 10 million Russians been “annihilated” by the Soviets throughout their 75–year history would have been a good thing—compared to what actually happened! That number in fact is much higher.

One last thing, small but poignant. Black describes Congressman Samuel Dickstein as a close friend of Wise. After the dissolution of the Soviet Union, however, it was revealed that Dickstein had been a paid agent for the murderous NKVD. This raises a lot of questions which Black doesn’t care to ask. Further, this knowledge—along with all of the books linked above—came out before the 2009 edition of The Transfer Agreement. Black has no excuse for ignoring such damning evidence against his case.

But what about the transfer agreement itself? Well, here’s where I start saying nice things about Edwin Black. All credit to him for writing an absorbing and well-researched history on this secret pact between Nazis and Zionists. When he is not mendaciously overstating the Nazi menace or eulogizing Jews for trying to destroy Germany, he’s actually quite level-headed and has a reporter’s knack for sticking to only what compels the narrative. His chapter entitled “April First” epitomizes excitement as it depicts, almost like a thriller movie, all the intricate twists and turns of one day in this riveting plot as both Germans and Jews lurch recklessly towards economic war.

On the Jewish side, the struggle boiled down to the belligerent, anti-Gentilic Eastern European Jews (as represented by Stephen Wise, the AJC, and Samuel Untermyer and his World Jewish Economic Federation) versus the more conservative and assimilated Western European Jews (as represented by B’nai B’rith and the American Jewish Committee). Where the former were calling for economic warfare the moment Adolf Hitler became chancellor, the latter were calling for calm and measured diplomatic responses.

Many of the men leading B’nai B’rith and the Committee were German Jews themselves or had friends and family back home. They understood that many of the atrocity reports (known as Greuelpropaganda) coming out of Germany at the time were either lies or gross exaggerations, which was a real sore spot for the Nazi leadership. In some cases, Jews had become victims of violent attack because they were Jews. In other cases, they were victims because they were communist troublemakers who refused to cooperate with Nazi authorities. And when atrocity-mongering reporters like Jacob Leschinsky picked up such stories, they weren’t going to be terribly diligent in making such distinctions.

The German diaspora Jews also understood how serious the Nazis were. If men like Wise, Untermyer, and others kept provoking them, they would retaliate either by making German Jews feel the brunt of the boycott or the brunt of oppression. Many of these Jews were desperate to stop the boycott.

Sadly, the Eastern European Jews won this struggle through will, charisma, and the ability to recruit gullible Christians to their cause. Within months, Jews everywhere were tightening the vise on Germany, hoping to make it crack by winter.

On the opposite side of the coin were the Zionists. Where most Jews saw catastrophe in the Nazis, Zionists saw opportunity. Black is honest enough to admit the ideological similarity between the two, which perhaps is why the Nazis tolerated Zionist Jews most of all. He actually undermines the Jewish supremacist default positions of people like Wise and Untermyer by approvingly quoting common sense from Zionist pioneer Theodore Herzl:

Where [anti-Semitism] does not exist, it is carried by Jews in the course of their migrations. We naturally move to those places where we are not persecuted, and there our presence produces persecution. This is the case in every country.

What we now know as Israel effectively began on March 25, 1933 when German Zionist Federation Kurt Blumenfeld horned his way into an emergency meeting with Goering and other German-Jewish leaders. Goering intended to pressure these Jews into stopping the international Jewish boycott—seemingly operating under the fallacy that they could do this by virtue of being Jews. And according to Black, they really did try.

The Zionists, however, were different. They wanted nothing from the Germans except leave to leave. Goering liked this idea, and promised to play ball as long as the Zionists could do what the other German Jews could not: bring Stephen Wise and Samuel Untermyer to heel. The problem was that in order to entice the 550,000 Jews living in Germany to depart for the undeveloped British-controlled Middle East, each emigre would need to possess the considerable sum of ₤1,000 (now worth £91,566.55 or $114,029) to qualify as refugees according to British law. They would also need to be able to keep a significant percentage of their capital. Two very daunting tasks, but the Zionists were up for the challenge.

This is the struggle Black depicts on the pages of The Transfer Agreement. In it we discover a marvelous array of subplots and subterfuge that, again, could support a decent thriller. Beyond the bitter rivalry among the AJC, the American Jewish Committee, and the B’nai B’rith and the obvious Nazi vs. Jew divide, we have German Zionist Federation director Georg Landauer pitted against shady independent businessman Sam Cohen. The former was a true believer and the latter, well, let’s just say he might have been more interested in rescuing German-Jewish capital than German-Jews themselves. He always seemed to stay one step ahead of the Zionists when it came to making deals with the Germans as well. Then you have the loose cannon ideologue Chaim Arlosoroff and his struggles with the “Jewish Hitler” Vladimir Jabotinsky and his Revisionist movement in Palestine. And, as competing alpha-Jews, Wise and Untermyer butted egos quite often.

Everything came to a head at the so-called Political Committee meeting in Prague in August 1933. Here, the world’s most powerful Jews were about to officially declare their anti-German boycott when the Zionists finally revealed the ace up their sleeve: the details of the transfer agreement. In a nutshell, Jewish emigres would leave the majority of their wealth in frozen assets called sperrmarks, which were managed by a Zionist-friendly bank. A collection of Nazi-friendly Zionist businesses (including the one owned by Sam Cohen) would then sell German goods in Palestine and other places, while German exporters would pay themselves with sperrmarks. It was a brilliant scheme, a win-win for the ethnonationalists. It also caused a great deal of kvetching among the Jews in Prague, not least of whom was Stephen Wise—because according to the transfer agreement they could have boycott or Zionism, but not both.

Given that Wise was such a villain throughout this narrative, his getting stymied in the end was satisfying.

To conclude with another chess analogy, there is something known in chess as a helpmate. This is a puzzle which challenges both players to checkmate one side in a certain number of moves. Thus, one player is actually working to checkmate himself. The Transfer Agreement is not quite that bad, but sometimes it does approach helpmate levels of suicide when it comes to Jewish apologetics and the Third Reich. A better analogy would be that Edwin Black is simply a poor player who ultimately captures fewer pieces than his opponent (i.e., the well-read, discerning reader) and ends up in a worse position than when he started. But he still manages to capture pieces. Yes, Nazis said and did things which are difficult if not impossible to defend nearly a century after the fact. So what? The people he champions said and did worse. And Black is not exactly in a hurry to tell us about it.

Often in The Transfer Agreement Black describes the international Jewish struggle against Nazi Germany as economic or propagandistic war. Stephen Wise takes it further in the book’s final chapter when on September 23, 1933, he hinted darkly of real war against Germany. He stated that boycott “is a weapon, but it is not the weapon. . . . The president of the United States and the prime minister of England can do more than a hundred boycotts.”

So war it is.

But this raises an interesting question: if the first casualty of war is always the truth, and the Jews are always at war, then when can we ever rely on Jews to tell the truth?