By Padraig Martin for Identity Dixie

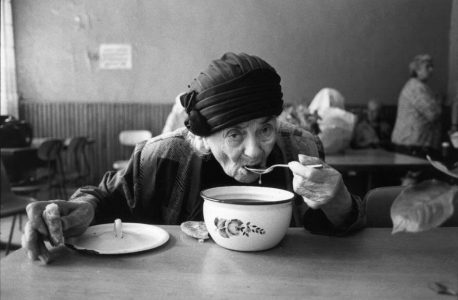

For the past forty years, and the better part of the past eighty years, Americans have enjoyed a remarkably stable economic life. This has been predicated on two pillars of fiscal policy: inflation management and United States dollar hegemony. That is about to end, and that end will be brutal for most Americans. The starving time is coming fast.

To begin, it is important to understand the machinations of American economic prosperity. Inflation management has been achieved through a number of tools, including interest rate manipulation by the Federal Reserve Board, the outsourcing of production to lower cost locations, highly functional supply chains, and stable oil supply and pricing. When monetary supply was tight (i.e., dollars were in higher demand, potentially triggering deflation), the Treasury Department, at the direction of the unelected Federal Reserve, opened printing presses to ensure the availability of more dollars. This action would often be coupled with a Federal Reserve move to lower interest rates, seeking to further suppress the value of that money. Until recently, neither party did so in a ham-fisted manner. Rather, once a balance was restored, interest rates would rise, printing presses would cease (or slowdown), and eventually the U.S. economy would balance itself. Such a balance kept inflation in check, never allowing the U.S. dollar to cheapen so quickly that the price of goods rose faster than manageable. This is why our recessions since 1944 have generally been mild compared to the Panic of 1837 or the deflation-triggered Depression of the 1930s.

Meanwhile, throughout this period of time, there has been a general move to reduce prices and inspire consumption through the use of lower cost manufacturing states (e.g., China, Taiwan, Malaysia, etc.). Televisions that cost thousands of dollars in relative terms twenty years ago, cost hundreds today due to innovation price curves and inexpensive production. Furniture, clothing, and various consumables have all become cheaper over time – both in price and quality. This was tied to a functional supply chain and stable fuel prices within global transportation markets. As long as American tax and regulatory policies encouraged foreign outsourcing, companies moved production away from the United States, increasing their profits. This only occurred, however, as long as the supply chain remained stable and fuel prices empowered transportation markets to move efficiently.

Given that oil is a dollar denominated commodity (at the moment), oil prices react inversely to dollar value fluctuations. If the U.S. dollar is reduced in value, oil prices rise and vice versa. The creation of the “Petrodollar” was not a real monetary instrument, per se. Rather, it was the development of a basket of currencies introduced by oil producing states to help guard against any collapse of the U.S. dollar itself. Still, the dollar is the primary instrument by which oil is purchased and priced. If you are German, for example, you purchase oil in U.S. dollars, even though you use euros on a day-to-day basis. The same goes for the Japanese who use yen. Whereas occasional state actors might take alternative currencies as a means of necessity (e.g., Iran), oil, as a global commodity, is denominated in U.S. dollars – even when oil producers convert those dollars into other currencies to enjoy reserve stability in the form of a Petrodollar. This is why the Americans never need to conquer a country to take its oil fields (e.g., Iraq); the Americans already dominate oil because they control the currency within which it trades.

Pulled together, even when the United States intentionally cheapened its currency, often to monetize its enormous debt – as well as the debts of its largest corporations (a concept I will get into in a moment) – other countries sought trade with the United States because it paid in U.S. dollars – a monetary instrument with no real global competitor. China, for example, was happy to take U.S. dollars for cheap goods and even pegged its own currency to the U.S. dollar to ensure its labor rates never exceeded the levels Americans were willing to spend for cheap products. The Chinese feared that foreign corporations might move away from China if their labor became too costly. In the early 2010s, China made a number of moves to market its population size as an alternative marketplace to the U.S., somewhat changing this dynamic (an article for another time). Regardless, throughout the shift to low-cost foreign labor, oil prices, while at times driven higher by American policy meddling or dollar manipulation, for the most part stayed steady. This all comes back to the U.S. dollar.

U.S. dollar hegemony is the result of the Bretton Woods Agreement of 1944. As the Allies realized the war with Germany and Japan was likely to end in their favor, a number of countries got together and determined that the post-war era would require some benchmark for currency and economic recovery. The United States, which suffered very little from the World War, and enjoyed a position as the world’s largest economy, held the most stable currency at the time. Consequently, the international banking order chose the U.S. dollar as the world’s reserve currency. Even after Richard Nixon decoupled the U.S. dollar from gold (another dollar denominated commodity), the U.S. dollar remained the world’s reserve currency due to the size of the American economy. That does not mean the U.S. dollar will be the strongest currency. The British pound, for instance, has greater value. It simply means the ability to access and trade a given item is fundamentally a product of an American monetary instrument relative to the value of other commodities and currencies.

Looking at the totality of the financial operating environment, one can easily see how this falls apart with a push. U.S. dollar hegemony is predicated on a global trust that the U.S. will pay its debts, will remain economically dominant, and will never manipulate its currency so badly that the currency becomes cheapened beyond repair. If that trust is broken, the potential exists for countries to seek other currencies that offer more assurances for long-term stability. As that happens, American decision makers at the Federal Reserve and the Treasury Department are faced with a choice: do nothing or react. If they react – such as moves to strengthen the dollar and reinject global confidence in the American currency – a new problem emerges: a debt trap that leads to an inflation trap.

The United States runs on usury. The most important market in the U.S. is Wall Street, whereby debt is effectively traded minute-by-minute. Functional stock markets are important. In theory, a stock is a share in a company that needs to raise capital to achieve a particular goal in an environment or market whereby traditional lending institutions, such as banks, are either not available, limited, and/or risk averse. Again, theoretically, the riskier the goal, the cheaper the stock, but the greater the upside potential should the goal be met, the less risky the goal, the more expensive the stock relative to its earnings, with marginal or stable returns. For the United States, Wall Street was critical to the emergence of its post-Revolutionary War economy. The early U.S. did not have a National Bank designed for mercantilist purposes like that of the United Kingdom or France. Early American businesses had no government banking institution at which to turn to get major projects off the ground for quasi-Nationalist goals, such as the British East India Company’s facilitation by the Bank of England. Early American businesses sold stocks to raise capital to achieve business objectives. Thus, today, the U.S., despite having one of the newer stock markets in the Western world, has the most dominant stock market. It literally invented modern capitalism by means of capital necessity.

What the stock market was never intended to do was replace traditional retirement vehicles, such as pensions. When the first investment retirement accounts (IRA) emerged, they were tools for upper middle-class individuals to park money for a rainy day, potentially growing at a rate faster than the rate of inflation through moderate risk returns. Bonds and inflation typically stay fairly close to one another. The average inflation in the United States for the majority of the past forty years was about 2.5% annually. The average Treasury Yield has been about 3%, and most recently, at about 2% (lower than our current inflation rate). Meanwhile, the average stock market return has been 8%. Let’s explore this by using the “Rule of 70” (i.e., divide 70 by your rate of return and you get an approximate number of years at which it will take to double your money). Someone who invests in cautious government bonds would double their money in thirty-five years (70/2 = 35); someone who invests in moderate risk stocks would double their money in less than 9 years (70/8 = 8.75). If you are retiring and want more purchasing power for the dollars you parked, stock markets became the way to go. Therein lies the problem.

Publicly traded, stock issuing corporations are generally indebted institutions. Rarely does a corporation earn a profit that enables it to pay its debts in their entirety. Rather, they leverage their sales and capacity to seek out banking loans and then use stock proceeds to ensure some level of liquidity necessary to meet the conditions of those loans (most often associated with various debt covenants). When interest rates are low, corporations benefit the most, because that means loans will cost less to repay. Conversely, when interest rates are high, corporations suffer. This is why bad economic news makes stock markets jump higher. Worsening economic conditions for the American people benefits stock-trading corporations. Why? Because there is a far greater likelihood that the Federal Reserve will reduce interest rates and potentially issue some level of quantitative easing (i.e., print more dollars), cheapening the value of preceding debt while making future debt more affordable. This is what is called monetizing a debt – lower rates and print more dollars to make current debt less burdensome relative to future growth, empowering an institution to borrow more. The federal government does this with the American national debt, and it has a cascading effect on American-based corporations. Like I said, the U.S. economy is predicated on usury. Unfortunately, thanks to 401Ks, American labor is tied at the hip to predatory corporations that benefit when they – American labor – is beaten down. If you want to retire comfortably, you need to root for an American downturn that helps a corporate bottom-line.

The Thread That Pulls It All Apart

Correspondingly, all of this is predicated on U.S. dollar hegemony. Shake up the U.S. dollar’s value and compromise the integrity of the American economy, suddenly alternative currencies are sought for various trades. If that occurs, the entire American financial system collapses. The only way to combat that is through interest rate hikes. By doing so, they make debt more burdensome to the American economy (the national debt) and the corporations that rely on cheap money. Depending on the severity of the dollar crisis, the Federal Reserve will continue to increase interest rates and tighten monetary supply until such time that a global appetite for the U.S. dollar and bonds returns. Here comes the trap they set for themselves.

Beginning under the Obama Administration, and largely kept through the Trump Administration, several rounds of quantitative easing and a period of sustained sub-1% interest rates made the dollar so cheap that it had the potential for full collapse. The only reason that did not happen is because there was no global competitor. The euro almost took its place, but systemic political issues and the lack of a strong central bank held the euro back from taking over. This week, things changed.

The Saudis announced early last week that they would consider taking the Chinese yuan as a form of payment for oil. That is huge news. Until recently, as stated earlier, countries purchased oil with dollars through conversions. If Saudi Arabia, a leader of the Organization of the Petroleum Exporting Countries (OPEC), decides to take Chinese currency (as it appears it will), it is only a short matter of time before other states in OPEC do the same. Soon, the U.S. dollar is replaced in the most critical economic market in the world. Oil makes the world go round. It is the reason for the supply chain stability we have generally enjoyed for more than forty years. Since the Russians, one of the largest producing oil states and a member of OPEC+, are already banned from U.S. dollar banking, additional states joining an effective boycott of American dollars would have a monumental impact on American fuel supplies as well as confidence in the U.S. dollar. But it gets worse.

The Federal Reserve will undoubtedly race to try to reimpose dollar confidence. As it does so, unlike preceding years, oil prices will not necessarily drop. If oil producing countries abandon the U.S. dollar – in the case of Russia, it was forced to do so – Americans will yield very little benefit at the pumps. Worse, corporations will have no choice but to cut costs and trim their labor pools. Why? Because stock markets will not tolerate earnings losses – they will demand labor cuts. So too will banks, who have pre-set debt covenants, usually with some labor and wage growth association to those covenants. Meanwhile, net borrowing in markets such as real estate will slow, putting construction workers and related industries out of work. In other words, a perfect stagflation storm is emerging. Unlike the 1970s, the U.S. is so deeply indebted, that the consequences of stagflation will be far more brutal than that which we experienced under Carter. Whereas in the late 1970s, the U.S. could spend its way out of debt, in 2022, any money we make will go to servicing a debt in order to maintain global confidence.

As I stated earlier, U.S. dollar hegemony is predicated on a global trust that the U.S. will pay its debts, will remain economically dominant, and will never manipulate its currency so badly that the currency becomes cheapened beyond repair. American policy makers have done the exact opposite. Our debt is so high that the interest to service that debt will exceed tax receipts, shaking confidence that we will “pay our debts.” We surrendered economic dominance to China a decade ago. Meanwhile, we have spent the past twelve-plus years cheapening the dollar through interest rate manipulation and quantitative easing. Now, we surrendered oil. Welcome to the inflation trap.

Typically, as the U.S. dollar strengthens relative to its preceding value, inflation is brought under control. To do this, one must control the price of fuel that is necessary to bring goods to market. It does not matter if your goods are cheaper relative to their cost the day before, if the oil necessary to move your goods costs the same or more. On Friday, 18 March 2022, the Indian government made its first purchase of Russian oil exchanging rupees-for-rubles. That is a complete bypass of the U.S. dollar hegemony upon which American markets rely upon as it pertains to a control of oil. In other words, the world is revolting against U.S. dollar hegemony and seeking global alternatives.

Why is all this happening? Hubris. The world just watched the United States weaponize its dollar hegemony to punish Russia for actions it does not like. Whether you agree or disagree with the invasion of Ukraine, the fact that the U.S. could exploit its power in such a way gave pause to other countries, most of whom still think in naturally, nationalistic terms. This has led a race to find alternatives that are less likely to be used as a political cudgel. American decision makers, however, never thought this would be possible and it happened at a time when the United States voluntarily surrendered its oil independence gained under the preceding administration. Thus, not only did the U.S. scare other countries through its actions against Russia, it did so at a time when its currency was relatively weak, its economy is teetering, oil prices are high, oil independence is lost, the national debt is unserviceable, and real unemployment remains doggedly entrenched due to draconian and stupid Covid lockdowns. Do you know what happens to populations to which this occurs? Historically, they either starve or revolt.

American politicians, drunk on power, coupled with American corporations, drunk on greed, have done what no other power could do in the past nearly two-hundred-fifty years: defeated us at home.